WAKING UP FROM THE TRANCE OF UNWORTHINESS

Building a true sense of self-trust comes from making contact with the deeper parts of our being, such as the truth of our loving, even when we sometimes act in ways we don’t like.

Many years ago, I began to focus on the urgent need for self-acceptance. In fact, I called it radical self-acceptance, because the notion of holding oneself with love and compassion was still so foreign. It had become clear to me that a key part of my emotional suffering was a sense of feeling “not enough,” which, at times, escalated into full-blown self-aversion. As I witnessed similar patterns in my students and clients, I began to realize that the absence of self-acceptance is one of the most pervasive expressions of suffering in our society. We can spend huge swaths of our life living in what I call the “trance of unworthiness,” trapped in a chronic sense of falling short. Though we’re rarely conscious of it, we continually evaluate ourselves. So often, we perceive a gap between the person we believe we should be and our actual moment-to-moment experience. This gap makes us feel as if we’re always, in some way, not okay. As if we’re inherently deficient. A palliative caregiver who has worked with thousands of dying people once wrote that the deepest regret expressed by her patients is that they hadn’t been true to themselves. They’d lived according to the expectations of others, according to the should, but not aligned with their own hearts. That speaks volumes. We can move through our days so out of touch with ourselves that, at the end, we feel sorrow for not having expressed our own aliveness, creativity, and love. So much of the time we’re simply unaware of just how pervasive that sense of something’swrong-with-me is. Like an undetected toxin, it can infect every aspect of our lives. For example, in relationships, we may wear ourselves out trying to make others perceive us in a certain way — smart, beautiful, spiritual, powerful, whatever our personal ideal happens to be. We want them to approve of us, love us. Yet, it’s very hard to be intimate when, at some deep level, we feel flawed or deficient. It’s hard to be spontaneous or creative or take risks — or even relax in the moment — if we think that we’re falling short. From an evolutionary perspective, a sense of vulnerability is natural. Fearing that something’s wrong or about to go wrong is part of the survival instinct that keeps us safe — a good thing when we’re being chased by a grizzly bear! Although this sense of vulnerability — of being threatened — is innately human, all too often we turn it in on ourselves. Our self-consciousness makes it personal. We move quickly from “Something is wrong or bad,” to “I’m the one who’s wrong or bad.” This is the nature of our unconscious, self-reflexive awareness; we automatically tend to identify with what’s deficient. In psychological parlance, this scanning for and fixating on what is wrong is described as “negativity bias.”

For most of us, our feelings of deficiency were underscored by messages we received in childhood. We were told how to behave and what kinds of looks, personality, and achievements would lead to success, approval, and love. Rarely do any of us grow up feeling truly loveable and worthy just as we are.

Our contemporary culture further exacerbates our feelings of inadequacy. There are few natural ways of belonging that help to reassure us about our basic goodness, few opportunities to connect to something larger than ourselves. Ours is a fear-based society that over-consumes, is highly competitive, and sets standards valuing particular types of intelligence, body types, and achievements. Because the standards are set by the dominant culture, the message of inferiority is especially painful for people of color and others who are continually faced with being considered “less than” due to appearance, religion, sexual or gender orientation, or socioeconomic status.

When we believe that something is inherently wrong with us, we expect to be rejected, abandoned, and separated from others. In reaction, the more primitive parts of our brain devise strategies to defend or promote ourselves. We take on chronic self-improvement projects. We exaggerate, lie, or pretend to be something we’re not in order to cover our feelings of unworthiness. We judge and behave aggressively toward others. We turn on ourselves.

Although it’s natural to try to protect ourselves with such strategies, the more evolved parts of our brain offer another option: the capacity to tend and befriend. Despite our conditioning, we each have the potential for mindful presence and unconditional love. Once we see the trance of unworthiness — how we’re suffering because we’re at war with our self — we can commit to embracing the totality of our inner experience. This commitment, along with a purposeful training in mindfulness and compassion, can transform our relationship with all of life.

It’s helpful to understand that when we’re possessed by fearful reactivity, we can be hijacked by our primitive brain and disconnected from the neuro-circuitry that correlates with mindfulness and compassion. We become cut off from the very parts of ourselves that allow us to trust ourselves, to be more happy and free. The critical inquiry is what enables us to reconnect — to regain access to our most evolved, cherished human qualities.

The gateway is the direct experience of the suffering of fear and shame that have been driving us. Not long ago, one of my students revealed that she felt as if she could never be genuinely intimate with another person because she was afraid that if anyone really knew her, they’d reject her outright. This woman had spent her whole life believing, “I’ll be rejected if somebody sees who I am.” It wasn’t until she acknowledged her pain and viewed it as a wake-up call that she could begin to stop the war against herself.

Once we recognize our suffering, the first step toward healing is learning to pause. We might think, “I’m unworthy of my partner’s love because I’m a selfish person.” Or, “I’m unworthy because I’m not a fun or spontaneous person.” Or perhaps, “I don’t deserve love because I always let people down.” We might experience feelings of shame or fear or hopelessness. Whatever our experience, learning to pause when we’re caught in our suffering is the critical first step. As Holocaust survivor and psychiatrist Viktor Frankl famously said: “Between stimulus and response, there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and freedom.” When we pause, we can respond to the prison of our beliefs and feelings in a healing way.

The second step toward healing is to deepen attention. It’s important to ask, “Beneath all of my negative thoughts, what’s going on in my body, in my heart, right now?” When we begin to bring awareness to the underlying pain, I sometimes call that the sense of “ouch.” You might even ask how long it’s been going on and realize: “Wow. I’ve been feeling not enough for as long as I can remember.” If that happens, try placing your hand on your heart as a sign of your intention to be kind toward yourself and your suffering. You might even tell yourself, “I want to be able to be gentle with this place inside me that feels so bad.”

For most of us, staying with the “ouch” can be painful and grueling; it can wear down our spirit and energy. The reason I suggest putting a hand on our heart is that a gesture toward ourselves that expresses comfort or healing has real power. If being with yourself in that way is uncomfortable, imagine someone who is truly wise and compassionate helping you; this can serve as a bridge to bringing the healing presence to yourself.

When we do this, a shift begins to occur. We move from being identified with the unworthy self to a compassionate presence that witnesses and is with the unworthy self. That shift is a movement toward freedom. It’s in that very moment when we become present and offer kindness — or the intention of kindness — to ourselves that real transformation begins to take place.

I’ve experienced many triggers for my own trance of unworthiness. One of the most powerful in recent years was a long stretch of illness. Not only did I feel sick, but I would often become irritable and self-centered, then stop liking myself for being a bad sick person. It felt as if I were not being very spiritually mature in dealing with my illness. The Buddha called this the second arrow. The first arrow is, “Oh, I feel sick.” In other words, just what is. The second arrow is the sense of unworthiness we inflict upon ourselves — in my case, being a bad sick person.

When I experienced a sense of personal failure, of not being a good person, I’d pause, put my hand on my heart, and imagine an understanding presence around me, pouring care through my hands. Sometimes I’d mentally whisper the words “It’s okay, sweetheart” or “I’m sorry, and I love you.” Although at first I was invoking a larger presence to offer care to the bad sick person, as I relaxed, it became clear that the loving presence I’d invoked was intrinsic to my own heart.

This process of reconnecting to our sense of goodness and worthiness that I’ve described is based on two key elements — mindful recognition of what’s going on inside us, and a compassionate response. Many people have found that the practice of R-A-I-N offers an easy way to do this:

•Risto recognize what’s going on. Pause and acknowledge all the thoughts and feelings of unworthiness.

•Aisto allow, which means we allow the thoughts and feelings to be there. We deepen the pause. We don’t try to distract ourselves or get away from what’s happening. We let it just be, so that we can deepen into the “I” of RAIN.

•Iisto investigate with kindness. We bring a gentle, yet interested attention to our experience. This is where we start loosening the grip of the trance. Here’s where you can put your hand on your heart and offer yourself a message of compassion, or open to receive the loving presence from the larger energy field to which we belong.

•N means not-identified. This may sound like a dry term, but it signifies true liberation.

When we don’t identify with that unworthy self, we’re free to inhabit our wholeness,

free to inhabit the loving awareness that was clouded over, but always there.

RAIN is a process of disentangling from the trance. What it really comes down to is mindful awareness with kindness. The more I practice RAIN in my own life, the less lag time there is between getting stuck and relaxing open into a larger, freer sense of being. RAIN has helped me catch the ideas and feelings that have to do with an unworthy self, and then to realize that I don’t have to believe them! The feelings are there, the thoughts are there, but the sense of who I am is beyond any limiting story of self. I’ve learned to trust the beingness that is here, a loving presence that isn’t stained or diminished by thoughts or feelings of unworthiness.

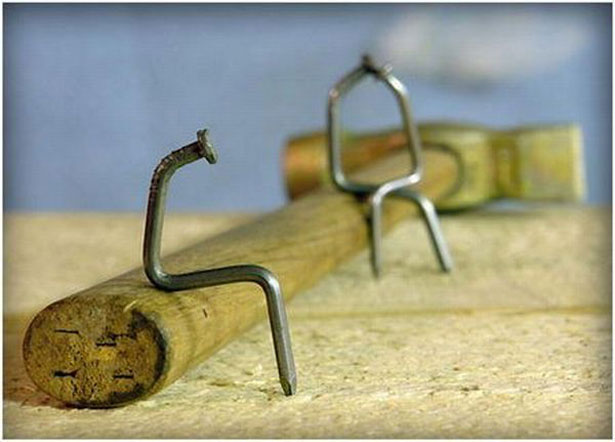

I’ve seen how, for myself and many others, even when we’ve been filled with self-hate or blame, we can find our way back to kindness. A metaphor I find helpful is to imagine you’re in the woods and you see a dog by a tree. You go over to pet the sweet dog and it springs at you suddenly — growling, with fangs bared. In an instant, you switch from wanting to pet the puppy to being really angry and afraid. Then you notice that the dog has caught its leg in a trap under a pile of leaves, so you switch again, from anger and fear to care and compassion. If we can pause and recognize that in some way our leg is in a trap, if we can see that the behavior we’ve been harshly judging in ourselves is coming from our pain, then we soften. We regain access to a natural tenderness toward our own suffering, and with that, open back into a more full and compassionate presence toward all beings.

Along with recognizing our vulnerability, self-acceptance arises as we deepen trust in our essential goodness. A woman once came up to me after a class and said, “I’m at war with myself because of the way I’m treating my five-year-old daughter. I’m bursting out in anger all the time and criticizing her, and I don’t deserve to accept myself. How can I trust myself if I’m doing this?” She was afraid that accepting or forgiving herself would just perpetuate being a bad mother. We all act in ways that are harmful at times, and reacting with self-punishment and self-hate is not a pathway toward more wise behavior.

I asked her, “Do you love your daughter?”

Tears sprang up as she answered. “Of course! I wouldn’t be so upset about this if I didn’t love my daughter.”

“Spend some time reflecting on loving her, what you love about her,” I suggested. “Feel that loving awareness in you, and get to know that as the place you can trust.”

That really resonated with her because intuitively she understood that while she couldn’t trust her ego, she could trust her heart. If we think we should be able to trust our ego-self, it’s not going to work. The ego-self is unreliable, out of control, causes trouble, strives, and is afraid. Building a true sense of self-trust comes from making contact with the deeper parts of our being, such as the truth of our loving, even when we sometimes act in ways we don’t like.

We are each on a path of awakening to loving the life that is here. Though we might call it self-acceptance, what we’re accepting is this feeling — this hurt, this sadness, this fear, this anxiety, and this sense of doing something wrong. As we grow to accept and embrace this living reality — its pleasantness, its unpleasantness — the illusion of a separate self dissolves. We discover the radiance and love that is our essence. The more we trust this essence, the more we recognize that same goodness and spirit in all beings. Our embrace of our inner life widens to an authentic and unconditional love for this living world.